Why Quicksilver¶

While Quicksilver is easy to use and very powerful, it’s not obvious how to use it and it takes a little while to realize its power. As a result it’s difficult to explain why Quicksilver is so great.

It took me about a week before I really “got” Quicksilver, and I think that’s pretty common. And then it took months of writing the manual to understand all the nooks and crannies. You can start off small and add to your knowledge slowly. The real power (and difference from Spotlight) is that there are multiple actions you can choose from, not just “open”.

The part that’s hard to describe is this: On a Mac today you do a lot of different things and go to different programs to do them (e.g., Safari for browsing, Mail for e-mail, Messages for IM, Contacts for contacts, etc). Even though the Mac is pretty consistent, these are all different applications and depending on what you want to do, you do different things, click in different places, use different shortcuts, etc.

Now imagine using Spotlight a lot. You would activate Spotlight, type the name of the thing you wanted to work with and hit return to open it in its app. Maybe it’s a bookmark that opens in Safari or a contact that opens in Contacts or a mail message that opens in Mail or a song that plays in iTunes. Once you do this, you use that app to do stuff.

With Quicksilver you have a consistent interface as with Spotlight, but with Quicksilver’s actions you can get to the next step and often that’s enough for the whole task. I can send a file to someone from Quicksilver alone. It will use Mail and Finder and Contacts to do the work in the background, but I just used Quicksilver. I can control Contacts with keystrokes to paste a friend’s address, from Quicksilver, without leaving the task I’m working on. I can move or copy files without having to manipulate Finder windows or dragging and dropping. I can do a Google search (or IMDb or Wikipedia) from within Quicksilver and have the results show in my browser.

All this (and more) makes Quicksilver a consistent interface for my Mac and that has some psychological effect that makes things seem even easier than Quicksilver is making them. Quicksilver is my Mac to me, and that’s hard to describe to someone who hasn’t played with it.

Nick Santilli summed it up well:

It’s Quicksilver. Don’t ask questions, just download it if you haven’t. Food will taste better, colors will be more vibrant, your computer will become something new and wonderful you never imagined.

You probably think I’m joking.

If you’ve been using Quicksilver for a while, you understand that he was completely serious.

Installation¶

Requirements¶

The latest version runs on macOS 10.10 or later. Previous versions are available for older versions of macOS.

Installing Quicksilver¶

From the Disc Image (.dmg) file:

- Download Quicksilver.

- Open the

.dmgfile and drag Quicksilver to your Applications folder. - Unmount the Quicksilver volume and delete the

.dmgfile.

Using Homebrew:

Homebrew is a package manager for OS X for installs, updates and uninstalls of most OS X software:

Open Terminal, type brew install --cask quicksilver. You can uninstall just as easily.

First Launch¶

Due to the way Quicksilver is built, macOS raises a code signing warning. The quickest way to get around this is to Control-Click or Right-Click the Quicksilver app in Applications, choose “Open” from the contextual menu, then choose the extra “Open” button that now appears in the warning dialog box. This only needs doing once, Quicksilver will then launch in future without further issue.

On first launch, Quicksilver presents some setup options (it can be rerun later with the Run Setup button in the Application Preferences). Choose a shortcut that activates the Quicksilver command window, or just accept the default, ⌃Space. Quicksilver will recommend plugins based on applications you have installed and other criteria.

Initially, Quicksilver shows no windows when it is running. Activate Quicksilver using the shortcut ⌃Space (if you accepted the default).

When Quicksilver starts it contacts qs0.qsapp.com to check for new versions. A security program like Little Snitch that monitors outgoing network connections might warn about this. It’s perfectly normal and benign.

Support Files¶

Quicksilver is usually installed in /Applications/ or ~/Applications/.

Like most macOS applications, Quicksilver stores its configuration information in the user’s ~/Library folder. As of 10.8, macOS hides this folder from the Finder by default. The Quicksilver action Make Visible from the File Attributes Plugin can be used to let the Finder show it. When first used, the following per user files and folders are created:

~/Library/Application Support/Quicksilver/Actions.plist- list of installed actionsCatalog.plist- the configured catalog sourcesMnemonics.plist- learned inputs, defaults and abbreviationsPlugIns.plist- the list of available plugins and how they are configuredTriggers.plist- the configured triggersPlugIns/- installed pluginsShelves/- where items on the Shelf and clipboards are storedActions/- add scripts here that implement actionsTemplates/- not installed but create this folder to use with the Make New… action

~/Library/Preferences/com.blacktree.Quicksilver.plist- various preferences and internal state~/Library/Caches/Quicksilver/- various state including indexes in binary files~/Library/Caches/com.blacktree.Quicksilver/- various state in binary files

It can also be useful to move or rename these while troubleshooting a problem. If plugins are not installing sometimes the permissions of ~/Library/Application Support/Quicksilver/ and the PlugIns folder inside it are wrong. If the owner is System, change it to your user account and restart Quicksilver.

Uninstalling Quicksilver¶

Move the application file to the trash. This leaves the configuration files. If you reinstall Quicksilver, your configuration will be restored. To remove all remnants of Quicksilver, use the Uninstall Quicksilver button in the Quicksilver’s preferences.

Getting Started¶

When I want to do something on my Mac, my first reaction is to use Quicksilver. Whether I want to send an e-mail, search for something on the web, open a bookmark, file, or an application, revisit a web page I looked at yesterday, pause iTunes, find a song, or virtually anything else, I type ⌃Space and activate Quicksilver to do it. That makes Quicksilver very powerful, but also a little difficult to explain. I’ll use an example of sending e-mail to my friend Ashish.

First, I could open Mail, type ⌘N to open a new message, type enough of Ashish’s name to have her address appear in the To: field, and then ⇥ to the Subject and continue writing the message. I could instead open Contacts, search for Ashish’s card, and ⌃-click (or right-click) on the e-mail address and choose Send E-mail.

This is how I do it using Quicksilver. I type ⌃SpaceA↩. That’s it.

Let’s walk through that. ⌃Space, at any time, in any application, activates Quicksilver bringing up the two pane window shown here:

When I type A, Ashish appears in the first pane because I often send her e-mail. Her picture appears because I have her picture in her Contacts entry (mostly because Quicksilver makes such good use of it). Also, another window appears below the main interface with other choices. If I kept typing, those would change to be some other choice, but since Ashish is what I want, I’m done. The second pane shows the Compose E-mail action which is what I want to do. This appears because it’s the most common thing I do with contacts. Typing ↩ performs the selected action so I see a new Compose Message window appear from Mail with Ashish’s address filled in.

Maybe using Quicksilver doesn’t seem that much easier than the other methods described, but the Quicksilver method is done entirely via keystrokes. There’s no mousing to the Dock to open a particular icon or having to select a specific field. Just type 3 keystrokes. Maybe the comparison seems unfair because I said some of the choices appeared so easily since I do this often, but that’s one of the advantages of Quicksilver. It learns what you do and makes your most frequent tasks easier. The other methods don’t learn and don’t get any shorter.

Now, let’s say I wanted to send a document to Ashish. Instead of choosing the default Compose E-mail action, I can tab to the second pane, type EMI to choose E-mail Item... (Compose). This opens a third pane which I tab to and type ~/Q to choose a document in my home directory that has “Q” in its name. Now the message window is opened with the attachment all set up. I can edit the message as needed and send it.

Now, say Ashish was expecting this document and I didn’t need to include any text in the message, just the attachment. I could choose the action E-mail Item... (Send) and then the message is sent in the background without opening Mail and without disturbing what I was doing before. The subject is set to the name of the attachment, and the body includes a short (customizable) sentence saying that the file is attached to the message.

The above works if I’m thinking, “I want to send Ashish this document”. Say instead I thought “I need to send this document to Ashish”. I can do this as well. Select the document in the first pane, choose the E-mail To... (Compose) action and then choose Ashish. I find these options to be the real strength of Quicksilver. It lets me easily do what I want, however I think of it at the time. I don’t need to change my thinking to how Quicksilver wants me to do things, and it learns from me and gets easier to use over time.

The amazing thing about Quicksilver is how flexible it is. Via a wide variety of plugins, Quicksilver can select just about anything on your Mac as an object and do potentially hundreds of different things to it. Of course, it can also do a lot more, get used to reading that.

Concepts and Terminology¶

Quicksilver is a modular application. This manual is organized around the things that Quicksilver can manipulate such as files, text, music, etc. Various Quicksilver concepts and facilities are introduced here so that the explanations in each following section can make use of them. A term introduced and defined is written like this.

These are the modifier key abbreviations used:

- ⌘ Command

- ⌥ Option

- ⌃ Control

- ⇧ Shift

Combinations are achieved by holding down one or more modifier keys and typing another key, such as a letter, number, or punctuation character. E.g., ⌘;, ⌥⌘S, etc. The arrow keys are shown as →, ←, ↑, and ↓.

The Quicksilver application runs in the background. By default there is a Dock icon, but no menu, menu bar icon, or other indication of Quicksilver on screen until it is activated with the shortcut ⌃Space. Though there are preferences to control the presence of Quicksilver in the Dock and menu bar. Preferences are available by typing ⌘, when Quicksilver has focus. (This is the Mac standard shortcut for opening Preferences).

The Interface¶

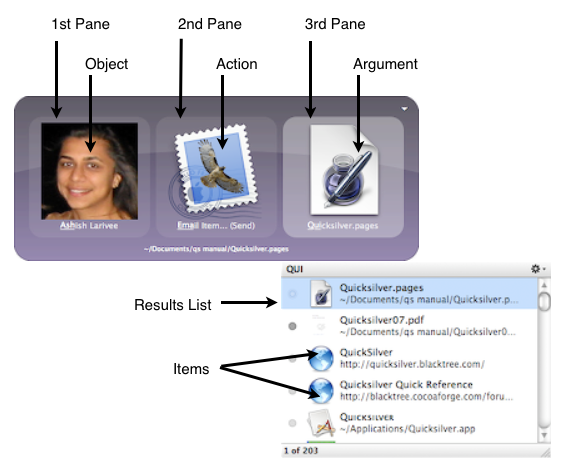

Quicksilver commands are entered via two or three panes containing respectively an object, an action, and if a third pane is needed, an argument. These are the terms used in this manual, but unfortunately other terms are used in some places in Quicksilver and in discussions online. The Primer Interface labels the panes Subject, Action, and Object. Some forum posts use Subject, Verb, and Object; and others use Direct Object, Verb, and Indirect Object. Much of the built-in plugin documentation refers to objects in the first and third panes as “items”. This manual uses the terms in the diagram above.

When typing in one of the panes, Quicksilver determines what items match, puts the top choice in the pane, and additional lower ranked matching items are shown in the results list. This happens for each pane, so the results list will contain objects, actions, or arguments depending on which pane is selected. The results list above is showing the possible arguments that match the entered text QUI. The term item is used for something appearing in the results list, regardless of whether they are objects, actions or arguments.

Plugins¶

Plugins are optional modules that are installed which can add objects, actions, or other capabilities to Quicksilver. Plugins are managed entirely from within Quicksilver’s Preferences including finding, installing, updating, enabling, configuring and removing them.

Plugins can be viewed and downloaded from qsapp.com, but the in-app system is recommended. The website will always show the latest version of the plugin, while the in-app preferences will take into account your version of Quicksilver and macOS and only show you plugins that will actually work.

The Catalog¶

The Catalog is the collection of objects that can be selected in Quicksilver’s first pane. Quicksilver populates the catalog by scanning catalog entries that are configured in the Catalog Preferences.

For example, there is a source for Safari which indexes bookmarks and history into the catalog. Each bookmark is an object in Quicksilver. So are files and folders in the home directory, contacts in Contacts, all the apps in the Applications directory, the playlists in iTunes, and many other things (provided the appropriate plugins are installed). Note that some plugins (such as Remember the Milk) allow Quicksilver to index things stored on web servers and not merely things on the hard drive.

Scanning to keep the Catalog up-to-date is done in the background at regular intervals (every 10 minutes by default).

!!! note "Relax" Many new users worry about a performance hit from frequent scanning. Don’t. The first part of the scanning process for any catalog entry is to ask “Has anything changed?” and the answer is almost always “No”. In general, only things that have been touched since that last scan will get scanned again.

Actions¶

A Preference pane shows all of the available actions. All actions work on objects, and actions are available based on the type of object selected. E.g., the Open URL action is only available for objects that are URLs. Actions that require an argument typically end in “…” and arguments are expected to be of a certain type. E.g., the E-mail To… actions expect the argument to be an e-mail address or contact. Actions with optional arguments usually end in “[…]”.

Some actions have a complementary action that reverse the object and argument ordering. Consider these two commands:

file, E-mail To… (Compose), address

address, E-mail Item… (Compose), file

Notice the names of the actions are slightly different (To vs Item). Many (but not all) action names hint at the type of argument they take. E-mail To… wants an address to follow. E-mail Item… wants some kind of item to send (like text, or a file). These e-mail actions are similarly named and many people don’t notice they are two different actions. In other cases actions are so differently named people might not notice they are related. For example, to perform a web search on a site like Google the two possible commands are:

site, Search For…, query

query, Find With…, site

There are also unfortunately some actions like Make New… which have no complement and don’t hint at what their argument type is. Explaining these actions is one of the reasons this manual exists.

Interfaces¶

Interfaces are configurable themes that change the appearance of the command window. They are installed as plugins and can be configured from the Appearance Preference pane. There are two built-in interfaces: Primer and Bezel. Primer (the default) is meant for new users as it labels a few things explicitly. Bezel is what has been shown so far and is used predominantly in this manual.

Matching¶

Objects, actions, and arguments are selected by typing. As each letter is typed the choices are filtered down from all possible choices to only those that match the input, and those objects are shown in the results list. You won’t see a typical “Search” input box that displays what you type. (If you’re doing it right, what you type will probably be unreadable garbage anyway.) Instead, you will see the characters you typed underlined in the top match.

The matching method is one of the strengths of Quicksilver. Matches can be by the beginning of the name (e.g., DESK for “Desktop”), or by initials (e.g., BA for “Browse Artists” which is an iTunes object), or some combination of those. As long as the letters you type appear somewhere in an object’s name in the order you type them, not necessarily next to each other, the object will match.

The more items (objects and actions) are used, the higher they appear in the list of results. After typing DES a few times, Quicksilver will start guessing “Desktop”, and if done often enough, it will start matching after just D.

!!! note "Always think in terms of abbreviations!" Much of the value of using Quicksilver is that, unlike other systems, you don’t need to type QUICKTIMESpacePLA, etc. to find QuickTime Player. Just type QTPL or even just QT. Quicksilver will quickly learn which abbreviations refer to which things in your head.

Children¶

Some items have Children, e.g., folders have files, contacts have phone numbers and addresses, musical artists have albums, etc. When an item has children there is a > to the right of the item in the results list. View the children (e.g., go into a folder) by typing → or /. The selected object then changes to the top child, and the results list shows the other children. Navigate these by using the ↑ and ↓ arrows, or better yet, by typing to match against this list. This is an easy way to navigate folder hierarchies, or any other hierarchies.

Triggers¶

Quicksilver’s matching algorithm makes finding something specific very efficient, and its ability to perform many different actions on objects makes it powerful. The main interface is efficient, but there are even faster ways to perform commands.

Triggers can be invoked at anytime, without having to first activate Quicksilver with ⌃Space. There are a few built-in triggers, and plugins sometimes add more, but you can add your own for common tasks.

Triggers can be configured to start or complete a frequently used command. Quicksilver comes with the ability to assign triggers to shortcut keys, but plugins are available to run triggers based on mouse events, gestures (drawing shapes on screen), and system events (like “Switched to Battery Power”).

Proxy Objects¶

Proxy objects work especially well with triggers. These are special objects which represent something on the system such as the currently selected text (which may be sent to a search engine) or the last downloaded file (which may be opened or moved) or the URL of the current page in Safari (which may be pasted into an e-mail message).

Collections¶

Collections are groups of objects built up either by using the comma trick, selecting all results with ⌘A, or grabbing multiple selected items from another application. You can use a collection to act on multiple objects at once. (e.g., copy multiple files, send an e-mail to multiple contacts, add multiple tags to a file, etc.)

Invoking Quicksilver¶

macOS uses the term “activate” to mean switching to an application (starting it if necessary). In fact there’s a Quicksilver action called Activate that does just that. The menu bar shows the menus of the active application. But if you hide its Dock icon (as most users do) Quicksilver runs in the background and unless it’s Preferences are open, it’s not the active application. Invoking Quicksilver, that is calling it forward and making it ready to use, is typically done by using the keyboard shortcut (by default ⌃Space) to bring up the command window. The first pane is selected and ready to find something in the Catalog via typing.

Selecting Items¶

With Quicksilver activated and the first pane selected, type some characters and an object will appear. To bring up a Contacts entry for Abraham Lincoln (doesn’t everyone have him in their address book?), type ABRAHAM, ABRAH, AB, or maybe just AL to select it. The trick is to keep typing the name of item until it appears in the first pane (and at the top of the results list).

If it doesn’t quite make to the top of the results list, scroll through the list and find the item and click it to select it. This can happen if there are several objects with the same name, for example a Contacts entry for Abraham Lincoln and a Finder folder named the same thing.

Quicksilver remembers what’s been typed and what’s been selected and learns to guess better as its used. If I type A and pick Abraham Lincoln’s Contacts entry, Quicksilver will start to guess it more often instead of the folder of the same name or “AirPort Utility” or “Adium” or other things that begin with “A”.

The matching algorithm that Quicksilver uses for selecting objects and how you can help it learn more efficiently are discussed below.

By default Quicksilver shows the results list after a short delay. This behavior can be changed to Immediately or Manually in the Command Preferences under “Show other matches”. There is also a choice to configure the spacebar to behave like ↓ or →.

Navigation¶

Quicksilver includes a lot of things in its Catalog, but to keep things fast, it doesn’t include everything on the system and (unlike Spotlight) it doesn’t index the contents of objects, just their names. Lincoln’s Contact entry may have his phone number and e-mail address, but typing them in the first pane won’t match the Contact. Quicksilver can navigate an iTunes music collection, but doesn’t include all songs and artists in the Catalog.

That’s not to say Quicksilver can’t use and manipulate these things. Once a parent object (in these examples, a contact or the iTunes app) is selected, typing → will move into the object and the results list will show its children (the contact fields or music collection). The results list displays items with children by showing a > at the far right. Navigating like this is often referred to as “right-arrowing into an object”. Similarly ← will go “up” and select the parent object. Quicksilver can navigate files and folders this way too. So while every file might not be indexed in the Catalog, the entire filesystem can be navigated using the arrow keys in Quicksilver. Since right-arrowing into folders is so common, the / key does the same thing as →, while ⇧/ is equivalent to ←. (That key was chosen because / is used as the separator between folders and files in a path. It’s also easier to reach on most keyboards.)

Alternate Keystrokes¶

A mouse or trackpad can be used to navigate the results list, but Quicksilver can do virtually anything from the keyboard. The ↓ and ↑ keys will move the selection in the results list down and up one item. For touch typists, the keystrokes ⌃N (next) and ⌃P (previous) will do the same thing and ⌃V and ⌥V will scroll the results list down or up one whole screen.

For Vim users, ⌃H, ⌃J, ⌃K, and ⌃L can also be used in place of the arrow keys.

Dealing with Typos¶

By default as of Quicksilver 1.5.1, the ⌫ key will remove a single character from your search string. If the search string is empty, typing will begin a new search (even if the previous selection is still shown), while hitting ⌫ again will clear the current selection.

New users should find the ability to remove a single character more intuitive, but for many years (prior to 1.5.1), there was no way to delete just a letter or two. The delete key ⌫ would clear the entire search, allowing you to immediately start a new one.

As you become more experienced, you may realize that simply starting over is much faster than correcting a mistake in the current search. For example, if you’ve built up years of muscle memory typing GRLI to find your grocery list, but you accidentally type GRIL one day, wiping the search with a single press of ⌫ and letting your fingers do what they’re used to is much easier than trying to figure out what you did wrong, how many characters you need to erase, what you need to then type to fix it, etc. The old behavior can be restored under Preferences → General → Extras.

The interface can be cleared entirely by pressing ⌫ with an empty search string, or by pressing ⌃U or ⌘X at any time. (The latter will copy the object to the clipboard.) If a Quicksilver pane is in text mode these behave slightly differently, as shown below.

| Shortcut | Regular Mode | Text Mode |

|---|---|---|

| ⌫ | removes one character from the search, or clears the selection | deletes one character |

| ⎋ | closes results list if open, or dismisses Quicksilver | leaves text mode |

| ⌃U | empties window, dismisses results list, back to top | nothing |

| ⌘X | empties window, dismisses results list, back to top, copies object to clipboard | deletes selection, copies selection to clipboard |

The Command Preferences has an option, “Reset search after” time. This is how long between keystrokes Quicksilver waits before reseting the search. So if it’s set to .85 seconds and it’s been 1 second since a key has been typed, typing another one will start a new search in the current context.

Combining Activation and Selection¶

There are faster ways to use Quicksilver too. You can activate it and put something in one or more panes at the same time. Triggers let you define key sequences, mouse clicks, and mouse gestures that will activate Quicksilver and fill in some panes and even execute commands immediately. These are discussed in more detail later but it’s worth describing two triggers now.

In the Triggers Preferences under Quicksilver are two predefined triggers: Command Window with Selection and Command Window in Text Mode. The first opens a command window with the current application’s selection in the first pane. This is typically text, though for the Finder this is one or more selected files or folders. Some other applications like iTunes also allow their non-text selection to be brought into Quicksilver. The second trigger will bring the selection into the first pane but will put that pane into text-mode so you can edit it.

Quicksilver installs a service available in other applications (look in the application’s menu under Services and you’ll see Quicksilver). The service is called Get Current Selection. It activates Quicksilver and puts the application’s current selection (typically text) into the first pane.

You can use this service from anywhere by selecting something and hitting ⌘⎋. You can change this shortcut in Preferences → Triggers → Quicksilver. If ⌘⎋ isn’t working for you, check in the Catalog under Quicksilver that Internal Commands is enabled.

Yet another way to put the selection into the object pane is to activate Quicksilver and then type ⌘G (for “grab”). This is slower than the other methods since you have to activate Quicksilver first, but since I learned it first, it’s in my fingers, so I use it a lot.

If Quicksilver is already running, clicking on its Dock icon will bring up the command window. If you drag and drop something onto the icon it will be selected in the first pane. This is convenient if Quicksilver is in your Dock, but people also put it in the Finder’s sidebar or toolbar. This is particularly useful if you hide your Dock and use Finder windows often. (I find the more I use Quicksilver, the less I use the Finder).

There are other, less obvious ways to select something in a Quicksilver command window pane. As discussed above you can type ⌘G to grab the selection of the frontmost application. You can also paste something into the pane with the standard key binding ⌘V, and you can drag and drop something into a pane as well.

History¶

The Catalog has two built-in presets for Recent Objects and Recent Commands. If Recent Objects is enabled, you can quickly navigate and act on your history.

| Shortcut | Purpose |

|---|---|

| ⌘[ | go back in history |

| ⌘] | go forward in history |

| ⌃⌘[ | show history in the results list |

Showing the history in the results list allows you to search for something using Quicksilver’s matching algorithm.

Recent commands can be searched for by name in the main Catalog, or if the Quicksilver Catalog Entries preset is enabled, you can search for and right-arrow into “Recent Commands (Catalog)”.

History is discarded when Quicksilver quits. To clear history without restarting, search for “Clear Quicksilver History” in the Catalog and run it.

Immediate Execution¶

You can create triggers that perform an entire command, like open an application or file. Triggers are great but they require you to pre-configure them. You can also perform a command by holding down the key you use to select a subject or action. For example, if you type AD to select Adium.app and hold down the D then Quicksilver will execute the default action which should be Open. As described above, for me typing A will default to the Contacts contact for my friend Ashish. I can activate Quicksilver and hold down A to open an e-mail message (the default action for a contact) addressed to her.

This trick also works for actions. If you hold down the last key you type to select an action it will execute it. So I can select Ashish in the first pane, tab to the second and hold down E to use the Edit Contact action. This method is a little risky if you don’t know what the action will be, but if you do it’s a little faster and there’s no trigger configuration needed.

To make it faster you can type the letter that matches an action with the ⇧⌘ modifiers while still in the first pane. So to edit Ashish’s contact entry I would activate Quicksilver, type A to bring up her entry and then type ⇧⌘E to have Quicksilver execute the command. This only allows you to use one letter to identify the action and has the same risk that you have to know what action will be run, but if you do, it can be convenient.

Holding down ⇥ for a while will execute the command, if for some reason you’d rather do that than hit ↩.

The Comma Trick¶

A non-obvious feature is known as the comma trick. The , key allows multiple items to be selected in first or third pane, and then a single action can operate on all of them with one command. This can move several files to the same place or address an e-mail to multiple people.

Activate Quicksilver, select an item, type , and then select another item. A collection of smaller icons accumulate at the bottom or left of the object pane depending on the interface used (the menu interface does not support the comma trick). Any number of items can be selected, after which ⇥ to the action pane and continue as normal.

Another way to select multiple items is with ⌘A. It will select all the items in the results list as if the comma trick had been used individually for all of them. If the results list is long this can take a long time. It’s most useful to operate on all the items in a small folder (e.g., deleting, moving, or tagging them all).

Collections can be browsed using ⌃[ and ⌃]. The currently selected object can be removed from the collection with the ⌫ key. ⌥, will remove the most recent item added to the collection, no matter what you have selected.

Filtering the Results List¶

The default behavior of Quicksilver is to filter the results list when searching. As keys are entered, things that don’t match are removed from the results and the remaining items are sorted based on how well they match what was entered.

There’s an often overlooked gear menu at the top right of the results list. It can change the search mode of the results list. Instead of filtering the results list can be set to snap to a match. The items remain sorted and as keys are typed the selected item is changed (and the list scrolled) but non-matching items aren’t removed from the list.

Sometimes these behaviors are known as narrowing (filtering) and selection (snapping).

- Filter Results - Filters the current results list.

- Filter Catalog - Filters, but also includes the entire contents of the top-level catalog. Lasts until you type ⎋ or activate Quicksilver again.

- Snap to Best - scrolls the results list to the best match but doesn’t remove non-matching items.

Helping the Matching Algorithm¶

Quicksilver learns what you do (and makes that easier to do) because of its matching algorithm. It remembers what commands you execute and what you did to call them up. Do them a few times and they get easier to call up because those objects and actions appear higher in the results. However if you do things that are similarly named it confuses Quicksilver and it won’t guess as quickly as it could. Fortunately you can teach it. Triggers, described above, are the fastest way to do things in Quicksilver, but there are only so many keystrokes you can remember. Here are some other techniques you can use.

If you activate Quicksilver and start typing into the object pane you’ll see a results list appear of items that match what you’ve typed. The order of the items is known as their rank. The first item is ranked 1 the second is ranked 2, etc. For objects, the rank is determined based on the score of the items. Score is computed based on how well an item matches what you typed.

Theoretically, items move to second place rank the first time they are used to match some input. The second time they are used they get ranked first. The circle to the left of the item indicates how well the item matches the typed input. The darker the circle, the stronger the match (i.e., the higher the score).

You can manually adjust the score of an item by ⌃-clicking on it to bring up a menu of choices. If you choose “Set as Default for…” then the selected item will match if you type the same abbreviation again. You can undo an abbreviation by choosing Decrease Score in the menu.

Setting a default works for what you’ve typed, but say you want to set as a default something that is mid-way in a very long list that you don’t want to scroll through. As an example say you want “Z” to bring up your Amazon bookmark and that if you type Z, Amazon is further down the list than you want to look. In that case, use the Assign Abbreviation action. Bring up the object you want in the first pane (www.amazon.com), choose Assign Abbreviation as the action, and in the third pane enter the abbreviation you want via text mode (Z). Now if you type that abbreviation in either the first or third pane, your choice will be ranked first. This happens because exactly matching an abbreviation causes the item to have a very high score.

!!! note

Abbreviations will only work if they match the input string in some way. You can’t set IRC to be an abbreviation for Colloquy.app because if you typed IRC, Colloquy would not appear in the results list. Say you don’t use Activity Monitor often and when you want it you can never remember its name but you think of the word “processes”. Searching for “proc” won’t work since those letters don’t appear in “Activity Monitor”. Synonyms were created for situations like this.

Actions in the second pane work a little differently. When they initially appear, their rank is statically determined by their order in the Actions Preferences. You can manually change the order in Preferences by dragging and dropping them. You can save time by making sure the action you use most often is automatically selected. Once you start typing in the second pane though, the order of actions is determined by the matching algorithm.

Synonyms¶

Continuing with the example above, where you naturally think of “processes” when looking for Activity Monitor, you can use synonyms to create an identical copy of something with a different name. In this case, you could create a synonym called “Processes” that refers to Activity Monitor. From then on, you can find it by searching for “proc”.

Details on setting up synonyms can be found in the Preferences section.

TextStart Ranker¶

A slightly different matching algorithm can be installed using the TextStart Ranker plugin and selecting it as the String Ranker handler in Preferences. In general it works better matching acronyms over continuous letters in the name of something. Specifically, it makes two changes to the algorithm.

The first is that it favors letters at the beginning of words more. E.g., if the input is AM it will match “Activity Monitor” over “Amazon” since two beginning of word letters are matched instead of just one. The second difference is that it favors input that matches a higher percentage of the words. So the input AM will favor “Activity Monitor” over “Audio MIDI Setup” since all the words are matched (2 out of 2) instead of two thirds of them (2 out of 3).